Intermittent Fasting Calculator

This intermittent fasting calculator helps you plan your fasting schedule. Whether you’re following a 16:8, 18:6, or any other fasting schedule, this tool helps…

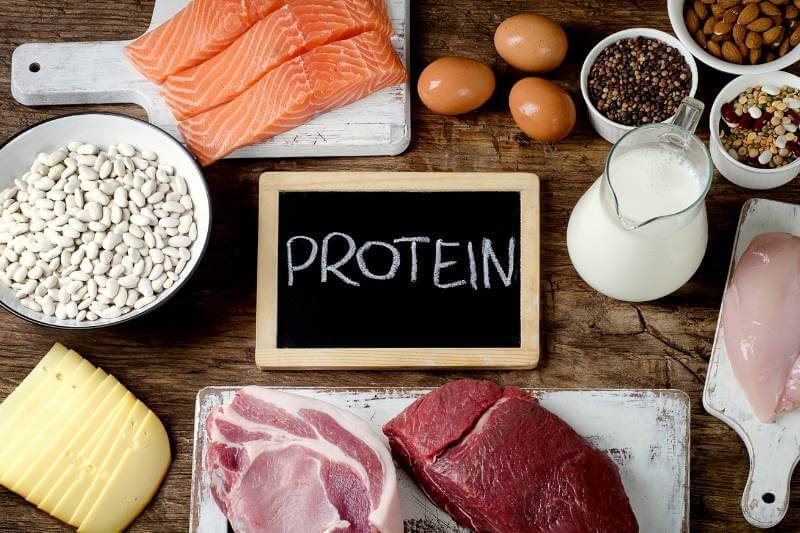

Protein Powder Price Per Unit Calculator

Buying a protein powder on price alone can be confusing (or just a blatant rip-off) due to differences in container sizes, serving sizes,…

Net Carbs Calculator

This free and easy-to-use net carbs calculator helps you track your carbohydrate intake effortlessly. Whether you’re following a low-carb or keto diet for…

Chicken Protein Calculator

This easy-to-use chicken protein calculator that will tell you how much protein is in that chicken you’re eating. Just choose the type of…

Meat Protein Grams Calculator

Wondering how to calculate grams of protein in meat? This super simple calculator is based on established food databases and will tell you…

400 Calorie Greek Chicken Bowl with 35g Protein

Looking for a satisfying, protein-packed dinner that won’t break your calorie bank? This Mediterranean-inspired Greek Chicken Bowl delivers bold flavors while keeping you…

Protein Calculator For Weight Loss

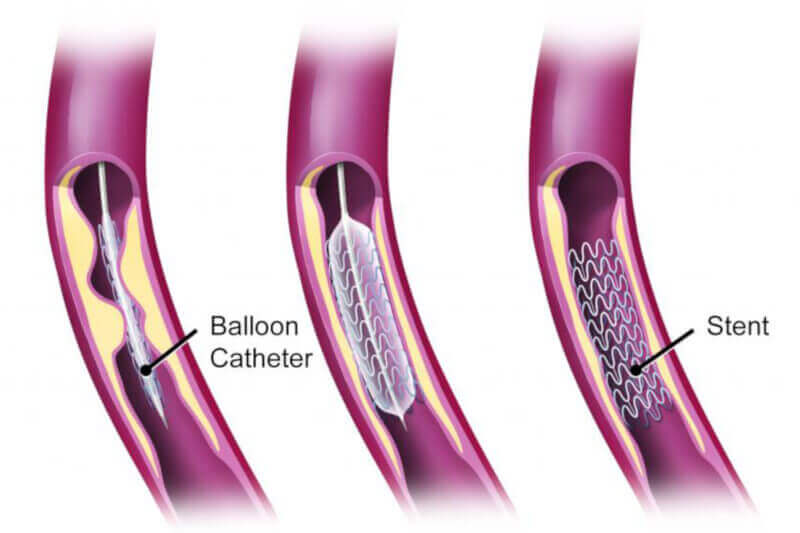

Exercise Guidelines After Angioplasty & Stent | 2025 Update

Can I exercise after an angioplasty and stent? Absolutely yes! Having worked many years in a hospital-based cardiac rehab unit as well as…

Declutter Your Mind in 10 Steps for Clarity and Focus

Detox Decision Making Tool

Macronutrient Percentage Calculator

Quick & easy macro calculator Enter your daily calorie intake and desired percentages and the macronutrient calculator will provide you with a breakdown…

7 Reasons Why I Cut My Social Media and Smart Phone Use

Your smart phone and, by default, your social media apps follow you everywhere. Technology has been intentionally engineered to embed itself in virtually…

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10): Assess Your Stress With This Online Tool

Pyroluria: Is It a Real Disease or Just a Myth?

Fat Mass Index | Because BMI and Body Fat Percent Suck

Have you ever heard of fat mass index (FMI)? Probably not. Most people haven’t. But you should be aware of it because it…

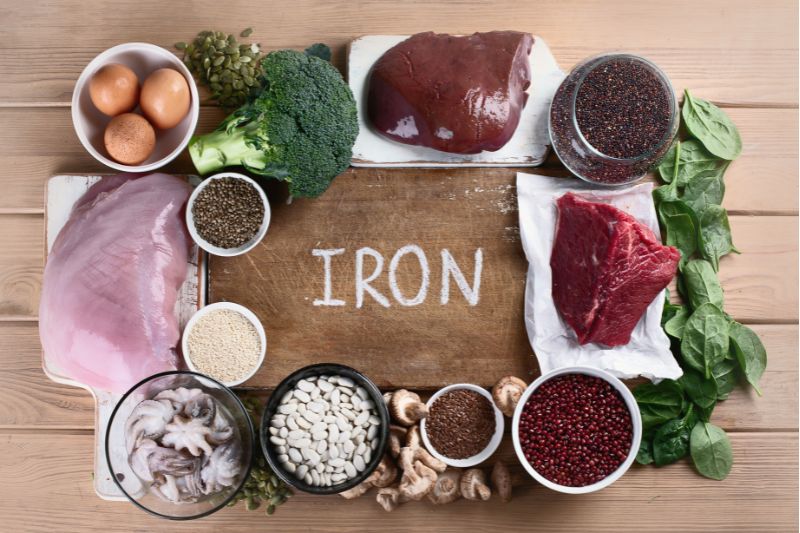

Iron Intake Calculator For Meat

This super simple iron intake calculator for a variety of meats is based on established food databases and will calculate the milligrams (mg)…

Addicted to your smartphone? Take the test!

Are you addicted to your smartphone? This simple smartphone addiction test is adapted from validated university research to help you determine if you…

23 Procrastination Hacks To Smash Your Goals

Are you tired of constantly putting off your dreams and goals, trapped in a cycle of procrastination and self-doubt? Procrastination is a universal…

Study: Smartphones Steal Our Attention and Reduce Mental Processing Speed

Total Daily Energy Expenditure Calculator

Your total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) refers to the total amount of energy you burn each day. There are a number of factors…

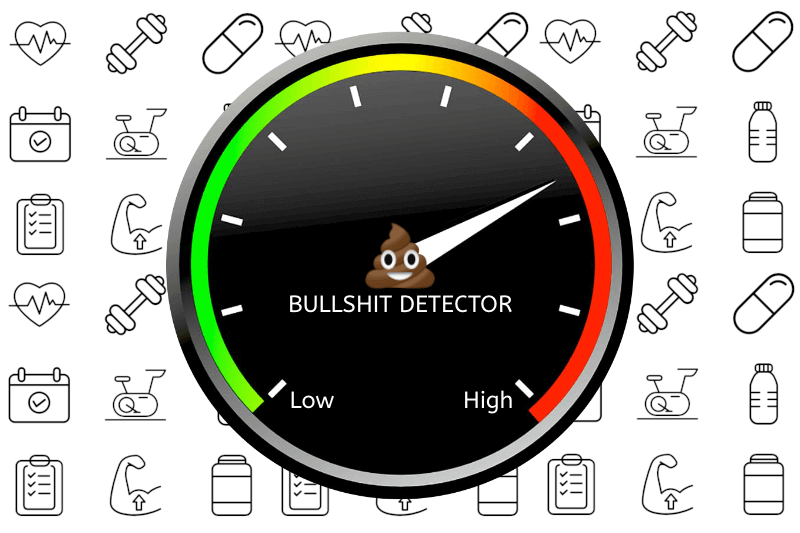

Interactive Bullshit Detector for Health Products & Services

How do I know if it’s bullshit? When it comes to health, there is a LOT of conflicting bullshit information which can leave…

Basal Metabolic Rate Calculator

Your basal metabolic rate (BMR) refers to how much energy your body burns each day (measured in calories or kilojoules) just to keep…

Lean Body Mass Calculator

The following lean body mass (LBM) calculator will provide you with an estimate of your lean muscle tissue and your fat mass based…

Body Adiposity Index Calculator

Body adiposity index (BAI) has gained attention in recent years as an additional metric to body mass index (BMI) and body fat percentage….

It Works Skinny Wrap Review

This It Works Skinny Wrap review is an August 2024 update to an earlier version from several years ago. The company has since…

Iaso Detox Tea Review

What is Iaso Detox Tea? Iaso detox tea is manufactured by Total Life Changes, a multi-level marketing (a.k.a. direct sales, network marketing, or…

16 Motivational Quotes To Ignite Your Determination

When life throws you a curveball, it’s normal to feel overwhelmed, discouraged, and ready to give up. We’ve all been there – facing…

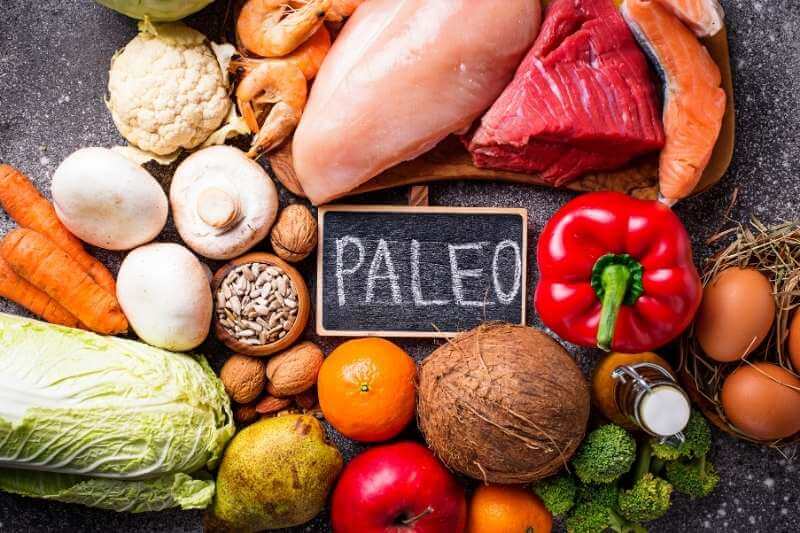

Paleo Diet After A Heart Attack? What You Need To Know

The Paleo diet (or hunter-gatherer diet) has lost its marketing momentum, but it’s still on the diet radar even now in 2024. If…

What Does “Clinically Proven” Mean in Advertising?

Caralluma Fimbriata Review 2024: Does It Help Curb Appetite and Promote Weight Loss?

Overview Caralluma fimbriata is a succulent plant native to India, Africa, Saudi Arabia, and Southern Europe. It has a long history of traditional…

Angry Too Often? New Study Finds It Could Be Bad for Your Heart

Study: Nature Engagement Linked to Reduced Inflammation Levels

Study: Excessive and Compulsive Smartphone Use Linked to Mental and Physical Health Issues

8 Ways To Get Shit Done – Even When You Don’t Feel Like It

Need to get shit done but really don’t feel like doing anything? That would explain why you’re procrastinating by reading this article! As…

Generation A: Unplugging the Social Media Addiction Epidemic

Social media addiction is real and it’s completely out of control. On the train to Sydney a few weeks back, I couldn’t help…

Does Psilocybin Cause Heart Valve Damage? A Review of the Research

Psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms, has been shown in research studies to provide relief for end-of-life anxiety and depression (Grob et…

Is Fruit Sugar Bad For You?

“Can I eat fruit?” “Will fruit sugar make me fat?” “I’m on a low carb diet so I cut out fruit because it’s…

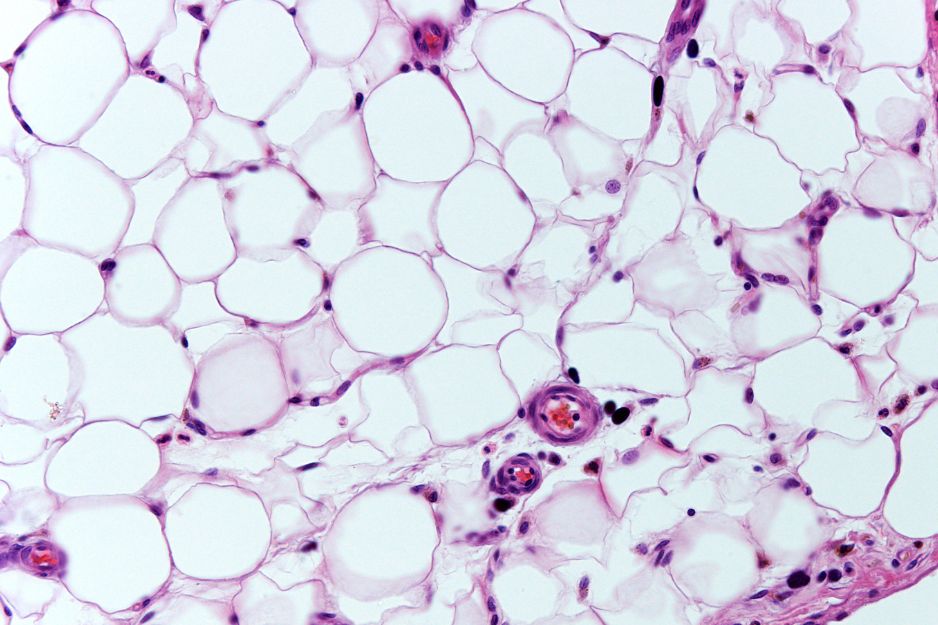

How Much Body Fat Should I Have?

I’ve run a LOT of DEXA body fat scans during my health career, but even with a trained eye, I can guarantee you can’t…

Body Wraps For Weight Loss: Do They Work?

Let’s get right down to the bottom line: do body wraps work for weight loss or are they a scam? In short: yes and…

How to Choose a Personal Trainer – Using Science!

Choosing a personal trainer in can be a daunting experience. Who is best qualified to help you? Who will deliver excellent service in…

CrossFit: An Independent Unbiased Review

CrossFit exploded onto the scene about a decade ago and since then has amassed a huge following – and a lot of criticism. But is…

Carbohysteria – An Open Love Letter to Carbohydrate

Dear Carbohydrate,I love you. I do. I’ve always loved you. From the moment I first set eyes on your chemical structure – C6H12O6…

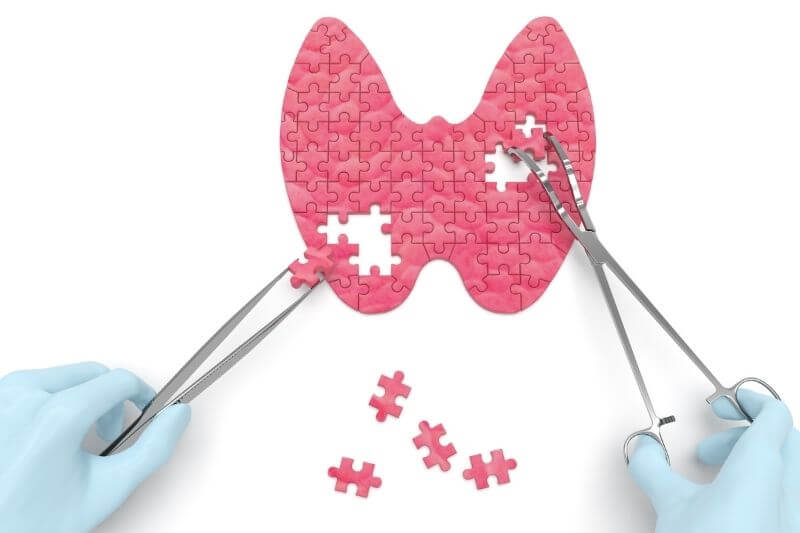

Exercise for Thyroid Disorders: Your Ultimate Guide

If you have a thyroid condition, exercise might be the last thing you feel like doing. But the truth is, exercise delivers numerous…

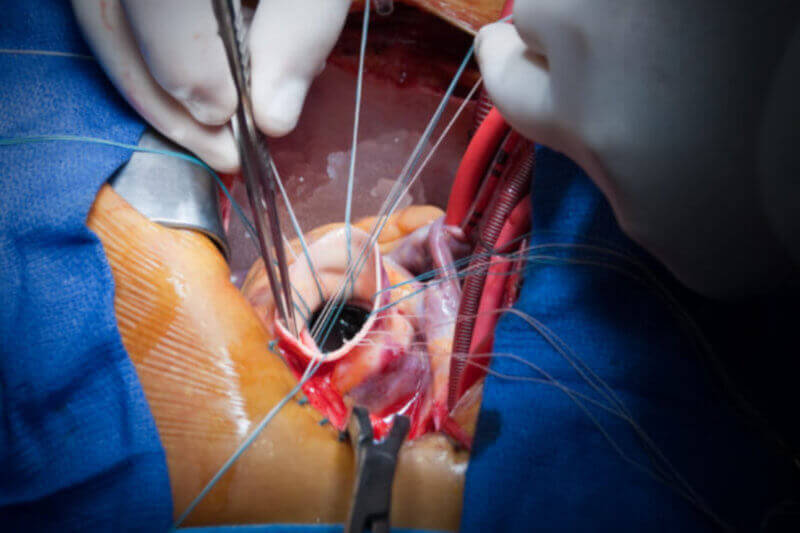

Heart Valve Surgery Exercise Guidelines

No doubt about it, heart valve replacement (or repair) is scary stuff. If you’re an active person, it may come as even more…

Four Sigmatic Mushroom Coffee Review

In this Four Sigmatic mushroom coffee review, I look into the product ingredients, scientific research, potential benefits, side effects and precautions, marketing claims,…

10 Tips to Get Off the Exercise Roller Coaster

Ever heard of the exercise roller coaster? No, it’s not the latest ab trimming infomercial gadget. The exercise roller coaster refers to when…

Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT): Incidental Movement For Permanent Weight Loss

Non-exercise activity thermogenesis sounds like a scary name. And in practice it can be even more scary to innocent bystanders! I get lots…

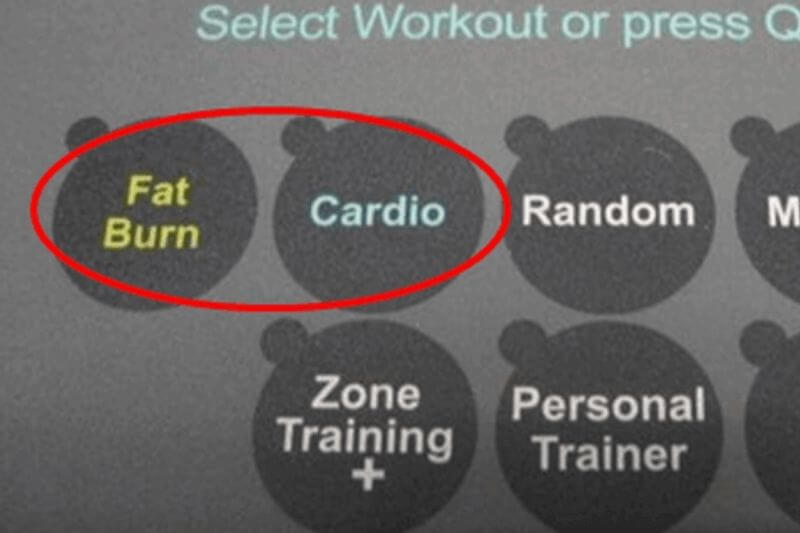

Fat Burn vs. Cardio Button: Which Is Best For Weight Loss?

Yearn for the fat burn! But do those “fat burn” buttons on exercise machines really live up to their names? What about the…

Exercise After Open Heart Surgery | Your Guide to Getting Started

Can I exercise after open heart surgery? How much exercise? How often? How hard? If you’re an avid exerciser (or even if just…

How to Exercise After a Heart Attack: Guidelines for Getting Started

Can I exercise after a heart attack? What kind of exercise should I do? How much exercise? What physical activities are safe? Should…