No doubt about it, heart valve replacement (or repair) is scary stuff.

If you’re an active person, it may come as even more of a shock.

You might be asking yourself, “how could this happen to me?”

You just want this nightmare behind you so you can get your life back to normal.

Common questions I hear from heart clients are:

- Can I exercise after heart valve replacement or repair?

- How hard can I exercise?

- When can I get back to running after a mitral valve repair?

- Can I lift weights after an aortic valve replacement?

The short answer to these questions is a resounding YES!

In fact, exercise is highly recommended after heart valve surgery, but you DO need to bear in mind some precautions and safety guidelines to reduce your risk of post-operative complications.

If you’ve had a previous myocardial infarction (heart attack), bypass surgery, or angioplasty with a stent then you may need to tailor your approach with your cardiologist.

Therefore the purpose of this article is to:

- Give you a brief overview of valvular disease;

- Discuss the main heart valve surgical procedures (Skip directly to this part);

- Provide guidelines for the immediate post-operative recovery period (Skip directly to this part); and

- Discuss key exercise recommendations for valve surgery patients (Skip directly to this part)

1) Overview: What is heart valve disease?

The normal heart

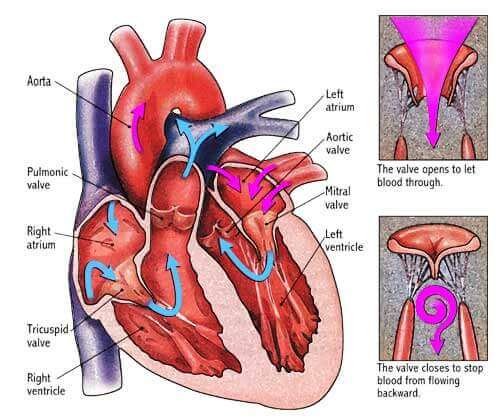

First, you have to understand that the heart is a pump.

There are two upper chambers called atria and two lower chambers called ventricles.

In between the atria and ventricles are one-way valves which allow blood to pass from the atria on top down to the ventricles at the bottom of the heart.

The mitral valve regulates blood flow from the left atrium to the left ventricle and the tricuspid valve regulates blood flow from the right atrium to the right ventricle.

The two valves that regulate the passage of blood away from the heart are called the pulmonic valve (to the lungs) and the aortic valve (to the rest of the body).

Normal valves close tightly to prevent blood flow from passing backwards through the heart.

The image below shows the normal anatomy of the heart valves.

Types of heart valve disease

- Valvular stenosis – in valvular stenosis, your heart valves become stuck together or stiffened from calcification. In this case, the heart has to work harder to pump blood through it. Over time, this can contribute to heart failure where the ticker wears out from the increased pressures.

- Valvular insufficiency – in this case, your heart valves become leaky and can allow blood to “regurgitate” backwards. This means your heart has to work harder to maintain a normal blood flow out to your body.

Causes of heart valve disease

There are a number of reasons why heart valves become insufficient or fail altogether including:

- Congenital defects – “congenital” is a fancy way of saying you were born with a valve abnormality.

- Disease or illness – two common causes of valve disease are rheumatic fever and bacterial or viral endocarditis. The latter is frequently attributed to dental procedures where bacteria from the mouth enter the blood stream and colonise the area around the valve.

- Unknown causes – in some cases, there is no identifiable cause for the valve problem.

Symptoms

No matter what the cause of your disease, there are a number of common symptoms which are associated with bad valves:

- Shortness of breath – if your heart is unable to pump sufficient blood to your body and lungs, then shortness of breath, fatigue, weakness, or an inability to keep up with your usual activities are logical outcomes.

- Lightheadedness – your heart’s inability to pump sufficient oxygenated blood to the brain might make you feel a bit woozy and even cause you to faint.

- Swelling – fluid accumulation around your lower extremities may occur due to the heart’s inability to adequately circulate blood not just to the body but also back up to itself.

- Chest pain or arrhythmia – in some cases, people complain of chest discomfort or may feel palpitations in their chest.

2) Common surgical procedures

So you’ve been to your cardiologist and it’s confirmed you need surgery to either repair or replace your leaky valve.

You will receive either a tissue or mechanical prosthetic heart valve depending on a number of factors including your particular condition, age, or ability or willingness to take blood-thinning medications the rest of your life.

Aortic and mitral valve surgeries are more common likely due to greater pressures found on the left side of the heart.

And it doesn’t discriminate, as even well known celebrities like Arnold Schwarzenegger and Barbara Walters have both had aortic valve replacement surgery.

Tricuspid and pulmonic valve surgery does occur but is comparatively less common.

The decision to repair or replace your valve will depend on your particular condition.

Most cardiothoracic surgeons prefer to repair the native valve (your own valve) if feasible since there is less risk of rejection.

The St Jude Medical has a short and informative article on surgery options.

Heart valve surgery video

The following short video shows a 3D animated video of aortic valve replacement surgery.

3) Post-operative activity guidelines

These guidelines refer to what I’ll phrase as “physical activity.”

I differentiate this from “exercise” because, in the post-operative phase, it’s just about getting up on your feet, puttering around, and putting some gravitational load on your body (not on flogging yourself back to health in a gym).

Remember the effect of heart valve surgery on your body is something like a controlled car wreck. It is a trauma on your body and you DO need to rest.

Give yourself permission to be human during the inpatient recovery phase which generally tends to last between four to seven days.

Full recovery from the surgery can last six to eight weeks.

You’ll probably spend a couple days in the intensive care unit for the first day or two after your surgery.

The team will diligently monitor your heart rate and rhythm, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, temperature, blood biomarkers, etc.

Once you’ve been cleared to leave the ICU, you’ll end up in one of the wards where they’ll get you up walking around the nurses’ station a few times a day.

Aside from getting your rest, one of the most important things you can do at this stage is early mobilisation.

It will help you shake off the effects of the surgery and bed rest and help you get back to feeling normal again.

If your hospital has on-site exercise physiologists or physiotherapists, have them work with you to get you moving around safely, even if you don’t feel like it!

Sternal incision site

Your chest incision is going to be sore and sensitive at this point.

Once cleared by your doctor, you should start doing some stretches and mobilisation of the shoulder girdle.

This will help promote range of motion and minimise stiffness around the neck, shoulders, chest, and back.

Also remember to be VERY diligent about keeping your sternal incision site clean.

Speak to your medical management team about their wound care procedures.

Failure to keep it clean can result in infection and another unexpected stay in the hospital.

Early activity program after discharge from hospital

Four to seven days have passed and you’ve finally been discharged from the hospital. Now what?

At this point, you’re now in the in-between stage between in-patient recovery and your regular exercise (i.e., the gym, running, sport).

During the immediate post-discharge phase, you MUST remember that even if you’re starting to feel better, there IS still healing happening on the inside.

The table below provides a graduated activity program to help you transition towards the exercise phase.

The overarching theme is that you do more frequent exercise bouts each day but for very short as-tolerated intervals.

Each week, you challenge yourself by adding about five to ten minutes to each activity bout but reducing the number of times per day you do them.

Your goal should be to graduate up to longer and longer continuous exercise bouts for fewer times per day (i.e, 1-2 bouts).

| Week | Min | Times x day |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3-5 | 6-8 |

| 2 | 5-10 | 4-5 |

| 3 | 10-15 | 3-4 |

| 4 | 15-20 | 3 |

| 5 | 25-30 | 2 |

| 6 | 30-45 | 2 |

| 7 | 60 | 1 |

4) Heart valve surgery exercise guidelines

Aerobic exercise

First and foremost, get your cardiologist’s clearance before you get back to the gym or your regular workouts.

Everyone’s case is different, so you need some assurance that you are medically stable before you start your quest for Olympic gold!

If you’re an athlete that had to go under the knife, then I can appreciate you want to get back to your training schedule.

In this case, I would suggest asking your cardiologist to do a maximal treadmill stress test.

If everything looks stable (i.e., no rhythm abnormalities, shortness of breath, or other complications), then you’ll likely be safe to get back to your routine.

Frequency – how many times per week can I exercise?

Coming off your graduated activity program I mentioned above, you should be able to do some exercise most days of the week.

I would suggest a minimum of three (3) days per week but ideally five (5) or more.

Listen to your body and remember to ease yourself back into it.

Heart valve surgery is hard on the body and you won’t be leaping tall buildings in a single bound overnight.

Intensity – how hard can I exercise?

When I work with clients, my aim is to figure out what their current exercise tolerance is.

I will put them on a treadmill and ask “if you were walking through your neighbourhood on a flat surface, how fast would you be walking?”

We then do some experimentation to find out what that speed is.

Once the initial habitual speed is established, say 4 kph (or 2.5 mph), then the goal is to match or slightly improve upon that intensity with each session.

So if you feel tired, try to match it. If you’re feeling particularly well, then try to bump up the speed by 0.2 to 0.3 kmh (0.1 to 0.2 mph).

I reference a treadmill in the example above, but you can apply the same concept to a bike, rower, elliptical trainer, or any other piece of equipment.

I’m not necessarily a massive fan of exercise equipment per se, but it is valuable in a rehab context because it allows you to QUANTIFY your progress.

If you don’t have any exercise equipment, then you can still get out and do the same thing by walking around your neighbourhood.

You can monitor your exercise intensity by heart rate or the talk test or rating of perceived exertion discussed below.

If you have a hard time finding your pulse, get yourself a heart rate monitor or a Fitbit (which also tracks your non-exercise movement habits).

Talk test

Medications like beta-blockers will blunt your heart rate response to exercise so the use of a heart rate monitor might not help you gauge your true intensity.

In this case, you can rely on what’s known as the “talk test.”

The aim is to be able to have a conversation with the person next to you while exercising.

You can huff and puff a little bit, but if you’re huffing and puffing and can no longer speak, then the intensity is probably too much.

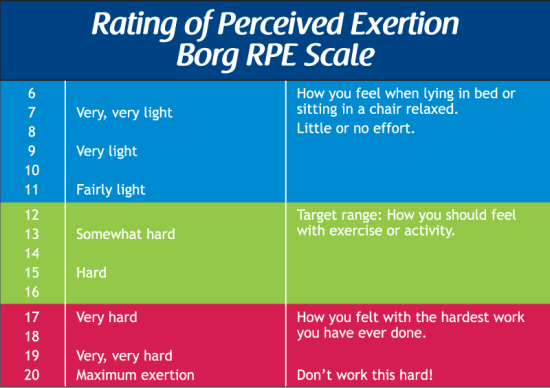

Rating of perceived exertion

The Borg rating of perceived exertion (RPE) 6 to 20 point scale is also quite helpful if you’re on beta-blockers (as in the talk test example above).

Counterintuitive as it may sound, a 6 to 20 scale is meant to correspond to a heart rate range of 60 to 200 (i.e., just add a zero).

So at rest, most people have a resting heart rate of around 60 beats per minute.

When you’re really pushing yourself, your heart rate would be up around 160 to 200.

The RPE scale requires a bit of a learning curve.

It trains you be become self-conscious of your subjective effort and more in-tune with your body (something a lot of people lose throughout their lifetimes).

If you’re participating in a cardiac rehab program, ask the staff to teach you the ins and outs of this scale.

Duration – how long can I exercise?

As with frequency and intensity, you need to ease into it.

Depending on how well you felt during your graduated activity program (discussed above in section 3), you can just continue on from where you left off.

Pay attention to how you feel the following day. A little bit of fatigue the following day is a good thing since it lets you know you pushed yourself.

But if you feel shattered and can barely get out of bed, then you probably went a little too long.

Gradually increase and adjust your duration by 5 to 10 minutes (as tolerated).

Types – what type of aerobic exercise is best?

There is no special or preferred aerobic exercise for heart valve surgery, but to answer this, I refer to a question I pose to my audiences during seminars: “what’s the best exercise in the world?”

Answer: “the one that you enjoy and will stick with!”

Whether you like to run, cycle, or swim doesn’t really matter.

All will challenge your heart and body to become more fit and efficient at delivering oxygen and nutrients to where they’re needed most (exercising muscles!).

From a recovery standpoint, try and do aerobic exercises that incorporate the large muscles of your body like your legs and hips.

Compound movements like these will give you more exercise “bang for the buck” and will put more stress on your body to improve as compared to movements which only work the smaller muscles of the upper body.

Aerobic exercise cautions

Warm-up

Make sure to give yourself a 5 to 10 minute warm up and cool down phase before and after each session (particularly if you live in an extremely hot or cold environment).

Medications

Blood thinning medications are frequently prescribed after heart valve surgery to reduce the risk of blood clots (which can lead to heart attack or stroke).

If you feel a bit wobbly on your feet after surgery, try to avoid movements which increase the likelihood of falling. If you bang your head, you are at increased risk of internal bleeding.

Environment

Following on from above, beware of environmental stressors like extreme heat, cold, or strong head winds.

All these can make exercise a LOT harder and really knock the stuffing out of you.

Be patient

Remember that even if you feel great, there is still healing happening on the inside.

Surgery is a trauma on the heart and the body so be nice to yourself and try not to overdo it with too much exercise too soon.

Your sternum might take up to a year to heal and get its strength back.

Signs and symptoms

Watch out for any out of the ordinary signs and symptoms.

Seek immediate medical attention if you experience chest pain, dizziness, light-headedness, shortness of breath or difficulty breathing, swelling in the ankles, extreme redness and oozing pus from your incision site, or anything else that is just doesn’t quite look right.

Early treatment can catch complications and stop them in their tracks.

Weight training (resistance exercise)

You should speak with your cardiologist or surgeon to find out if weight training is right for you and to get final clearance.

Lifting weights, particularly heavy weights, can cause a sharp spike in your blood pressure which, depending on your individual condition, may or may not be safe.

Provided there are no surgical complications or limitations in your particular condition, then you should be able to ease back into weight training.

Frequency – how many days per week can I lift weight?

Don’t try to be superman (or superwoman) after valve surgery. Start off with two to three times per week and gradually increase as tolerated.

If doing regular aerobic exercise, then remember the accumulated effect of aerobic and weight training might leave you drained.

Try to experiment to see how you can fit them together into a training regimen.

Intensity – how much weight can I lift and how hard?

If you’re just getting back into the weight room, start off with light weights and gradually progress from there.

Sets and reps will also need to be adjusted as tolerated.

Start with 4 or 5 kg (10 lb) or less during the first four to six weeks of recovery.

For example, you might use light dumbbells for your upper body exercises and maybe just body weight for squats and lunges.

Monitor for extreme soreness and adjust the weights up or down by 1-2% as tolerated.

Sternum and weight lifting

One of the main concerns most people have is whether or not the sternum can handle it.

In this case, there is an element of common sense. The sternum can take a year before it’s quite strong and ready to withstand heavy resistance placed on it (i.e., bench press).

In the immediate post-op phase, you can probably get away with lower weights and intensities and

Use light resistance in the beginning. It is far better to use light weights and learn proper form up front than start off with heavy weights and sloppy form.

Duration – how long can I lift weights?

Start off with shorter weight sessions of approximately 20 minutes and gradually progress as tolerated.

Long, drawn-out sessions can leave you exhausted and less likely to be compliant with your regimen.

And, as I mentioned above, if you’re doing aerobic training, then you’re going to have to fit it all into your schedule.

Types

There are no shortage of weight training options on the market: circuit training, Cross-Fit, high intensity interval training (HIIT), free weights, machines, body weight training using the TRX.

How do you know which one is right for you after surgery?

If you’re still in the early phases of recovery, err on the side of caution and do lighter weights and more reps.

As you get stronger (and with your doc’s approval), you can graduate to the more intense workouts.

Weight training cautions

Weight training requires proper form and breathing technique to help minimise sharp spikes in heart rate and blood pressure.

Remember to exhale on the exertion and avoid excessive breath holding and straining.

I would suggest working with a clinical exercise physiologist or trainer with experience working with cardiac clients.

As with aerobic training, you might be prescribed blood thinning medications to reduce your risk of blood clots.

You will need to be extra careful if there is any risk of your being hit by weights or someone else since these meds can increase your risk of internal bleeding.

Take home message

You can exercise safely and effectively after heart valve surgery provided you are medically-stable and have received full clearance from your doctor.

With proper precautions and a slow and gradual approach, you will be able to work yourself back to full health.

Be on the look out for any signs or symptoms that could be early warning signs for complications.

Now get back to living!!

Sir,

I am M.S.Patil and I’ve had open heart surgery on 12 June 2015. My pulmonary valve was corrected by “Valvotomy” to get rid of severe pulmonary stenosis. It was 110 earlier and constant. Now, after surgery, I feel quite well. The pulmonary pressure is now 25mm. In your article, you answered my questions. I am doing regular exercise at home with an RPE of 12 to 13. My cardiologist has given clearance to do resistance training instead of going to the gym. Now, can you please advise me, I want to do safe exercise to build my strength. I’ve started doing this exercise only after surgery. Now I’m 51 years old. Is it possible for me to build strength after open heart surgery from doing regular exercise? Thanks.

Hi Maruti,

Thank you for your comment. Whilst I cannot give you any specific routine or weight training regimen by way of the internet, I can say that it sounds like you have done everything right. In answer to your question, you can definitely build strength after your surgery, but I would advise working with an exercise physiologist or personal trainer to help show you safe exercise and breathing techniques. Once you have that, then you can go off on your own and build your strength. If you have any signs or symptoms, you should make sure to report them to your doctor to make sure there is nothing more sinister happening. Obviously if you’re having chest pain or anything else, go to the hospital. But safety first. I have worked with a lot of people who had heart attacks and open heart surgery and were able to lift weights and build strength, but you must always be safe first! Hope this is helpful. Kind regards, Bill

Hi Dr. Bill Sukala

One year is Passed, after my open heart surgery I was doing regular exercise as you have advised, (in your blog). Now I am feeling healthy, or I think now I can join gym for strength training.

During my complete one year exercise Program, I have maintained, 25 minute Cardiac Rehab Exercise, 4 mins, Stair Climbing Exercise, I used to go up stairs to my House on the 9th floor, every day after finishing my 20 minites walking exercise.

Initially I used to stop at 3rd floor then 6th floor, then 9th floor. Now I am in position to go up to 9th floor non stop. Nowadays I heard (read from internet) about HIIT exercise. Is it possible for me to do this HIIT. ?

I am thinking of doing sit ups (Sit and Stand). With 20 sit ups My heart beats goes up to 168 bpm. This happens within 40 sec. time, and again I reapet this after resting for 2 minites, is it ok? Please advise.

Hi Maruti,

Congratulations on feeling better after your open heart surgery. Regarding joining a gym and doing high intensity exercise, I would first advise you to speak with your cardiologist or whatever doctor is managing your cardiac care. I cannot legally give you a yes or know as to whether HIIT is right for you since I am not familiar with your entire medical history. Based on the information you have provided, it sounds like you have developed a good level of fitness. If your doctor can perform a treadmill stress test that pushes you to a high intensity and you do not have any abnormal changes in your ECG, then your doctor may give you clearance for performing HIIT. Keep up the good work. Kind regards, Bill

Hi Dr Bill,

I had my open heart surgery in 2013, i just wanted to know what kinda exercise i can do, im feeling abit over weight now and i want to lose it esp my tummy and love handles. can you give me advise please.

Hi Dr. Bill Sukala,

My name is Gabor Vasko. I am a 30 years old male and was doing sports my entire life. I had an aortic valve reconstruction on 20th of April in 2016. The surgery went well, I had zero regurgitation right after the operation then it progressed to minimal. 9months after surgery which was my 3rd follow up with my cardiologist they said the regurgitation is a little bit bigger but it’s normal. My fear is that the regurgitation will get worse quicker due to weight lifting, quicker than it would without me doing any exercise. I also run 10k once or twice a week and I do rock climb as well. My left ventricle was a little above 70mm before the surgery and now is 60mm. Is it possible that the regurgitation will get worse quicker due to weight lifting? I am also afraid that if the regurgitation gets worse then my left ventricle will start to get bigger again and I will have to go through another surgery a lot sooner than I was expecting. I go to the gym three times per week and either run or rock climb twice a week. Your answer is greatly appreciated. Best regards, Gabor Vasko

Hi Gabor,

Thank you for taking the time to leave a comment. While I cannot provide any medical advice (I’m an exercise physiologist), I think it’s important that you discuss these specific concerns with your cardiologist and/or surgeon. You’re clearly an active person and this is a part of your quality of life. I can’t say for certain if the regurgitation will get worse, as that’s something that can only be answered by your docs who are most familiar with your specific situation. If we play devil’s advocate and your regurgitation does get “worse,” then the next question is if it is clinically meaningful to the extent that it will cause symptoms and require you to have another surgery. Perhaps if it does get worse, it could be a very small change over a very long time. But again, this is something you’ll need to ask your doc. Based on the information you’ve provided, the cardiologist still said the regurgitation was within normal limits. I think provided you have good communication with your docs and you go for regular check-ups along the way, then you will be able to live your usual active lifestyle. Kind regards, Bill

Thank you very much for taking the time and answering my question. The problem is that it’s hard to find someone who can tell me exactly what is ok and what is not considering sports and exercise. I guess it’s not possible to tell someone exactly what is too much exercise, or too heavy weights. My doctors are great and I do talk to them regularly but my problem is that they can’t give me these answers, only basic guidelines and I just want to make sure that whatever exercise I do will not worsen my symptoms quicker. Again, thank you very much for taking the time answering. Best regards, Gabor Vasko

Thanks Gabor,

I can certainly understand your frustration, but when it comes to the ticker (or any medical condition for that matter), there are only guidelines but no catch all for every single person and condition. But there are people who break the mould and do some pretty incredible things despite underlying medical issues. I had a guy in my cardiac rehab program who was an elite cyclist, despite having had three heart attacks. He had so much damage to his heart muscle that he had developed congestive heart failure with a very low blood pressure. But amazingly, despite how sick his heart was, the rest of his body was so well-conditioned that it compensated for his heart. His blood pressures were anomalously low, like 60/40 at rest and during exercise he’d get up to a whopping 90/50 or so. The cardiac rehab staff talked to his docs and told them about how much exercise this guy could tolerate. They basically said under any other circumstances, they’d never recommend that amount of exercise, but in his case, it was “normal” for him.

The moral of the story is, work closely with your docs and get on with your life. Exercise and go back for regular checkups. Remember that, as with the guy in the above example, it’s not a one-size-fits-all when it comes to exercise with heart valve surgery. The docs need to take on board the fact that you are young and athletic. Those factors change the landscape a bit for you as opposed to someone who is 65 years old, never exercised, and has other medical conditions.

Hope this helps provide you some peace of mind.

Kind regards

Bill

Hi Dr. Bill Sukala

I am M.S. Patil, I have had my Open heart surgey on 12th June 2015. I am doing my Regular

cardiac exercise & I tried to increase the intensity of my Home Exercise gradually, In my Last E-mail, in which I asked you my ambition to build a body strength. I was thinking to join Gym, but instead I tried to follow Cardiac Rehab Exercises by getting downloaded & doing it regularly at home. I found improvement in my capacity. I used to check my heart rate & Blood Pressure almost Daily, I am thinking that, slowly my heart capacity will increase, so I am Trying to Push myself hard but slowly. Today I just Read the E-mail queary of Mr. Gabor, & I feel Mine is also same case, The correction of Pulmonary Valve, One Day I checked all my reports, & found that, other than this ” main Pulmonary Stenosis” Which was corrected, there are still other problems present like Mild Mitral, tricuspid regurgitation & moderate Pulmonary Hypertention is Present, Also Grade I Diastolic dysfunction is present.

My worry is, Is it possible to minimise this regurgatations by doing regular exercise. ? My regular HIIT Training includes 1) going up stairs non-stop up to 9th floor, it takes two minutes, & 2) doing Sit-ups ( sit & stand) fourty times in a length it takes 45 sec. & in both case my Heart beat reaches above 150 BPM. Please advise.

BEST REGARDS M.S.Patil

Hi Maruti,

As I mentioned to Gabor and most people who post questions in this forum, I cannot provide specific medical advice to anyone because I am not familiar with each person’s specific situation. It’s important to understand that there is no single “right vs wrong” answer that will apply to everyone. Yes, we do know that exercise is good for your health in most cases, but if your medical condition is not stable, then exercise can pose additional risks to your safety. So I would suggest speaking to your cardiologist and making sure that you are medically stable and that you have proper clearance from your doctor to participate in higher intensity exercise. I have worked with many patients who’ve had surgeries similar to yourself and Gabor and have gone on to lead very active lives. But again, it is very much dependent upon each person’s individual circumstances and must be cleared by the doctor. Also be aware that certain medications can have an effect on your body that may make higher intensity exercise safer (in terms of reducing exercising heart rate and blood pressure). Whilst I am not a fan of prescription medications, there are certain circumstances where they can be helpful to minimise risk and ensure your safety. Hope this helps. Kind regards, Bill

Hi Dr. Bill Sukala

Again I am M.S.Patil. Had open heart surgery in June 2015 for severe pulomanary stenosis. As I have written you before three times, I am doing regular exercise to build my strength. I tried to increase the intensity gradually. I was very happy and confident until March 2017. But this month I fell sick due to a full day of exertion and exposure to very hot temperatures.

This is a set back to me and I lost my confidence. I started to take a break in my regular exercise. In the month of April and May 17 I started feeling like i am in depression.

I don’t know what goes wrong? My weight which has stayed around 72 kg and practice doing 2 1/2 hours daily exercise in morning in my house has got collapsed.

Now my weight is 69.5 kg and I have almost stopped my exercise. And now thinking of doing

meditation yoga.

Please advise what to do?

Thanks

Maruti Patil

Hi Maruti,

First off, remember that you’re only human and whether or not you had the surgery, life is full of emotional ups and downs. If you are feeling a sense of depression, I would strongly advise you to talk to your doctor and perhaps seek out counselling services to help you address the underlying issues that may be causing your feelings of depression. Remember, that reaching out for help is a sign of STRENGTH and NOT weakness.

Going through open heart surgery is a very difficult process and it is not uncommon to have changes in mood in dealing with major medical issues. You might also find that doing meditation and yoga will help you find some mental and emotional peace to put you back on a healthy track back to your physical exercise.

So I would advise you to do the following:

1) Talk to your doctor and discuss your concerns in detail

2) Speak to a psychologist or social worker with experience in helping people with medical concerns (like open heart surgery).

3) Continue with your meditation and yoga which can help you keep fit and help calm your mind.

4) Be nice to yourself and remember you’re only human (we all are)!

Warm regards,

Bill

Hey Doc this is a great article. Ive spent the last 8 weeks searching the internet everyday for answers. Im 41 years old and had my Aortic Valve replaced 8 weeks ago. Ive been a CrossFitter for 5 years prior to surgery. My last 5k run was 20:43 pre surgery when I started noticing symptoms worsening so a follow up to the Cardiologist led to a catherization which ultimately led to Valve Replacement 2 months later. Im a smaller athlete only 5’4 about 150 lbs. The body weight movements ie pull-ups, muscle ups, hand-stand push-ups, is where i do best. Not much for the olympic lifts and throwing Big weights around. The fact that i was in such great shape before surgery help with a speedy recovery. Now 8 weeks out ive started to train again keeping the intensity low but also incorporated some body building movements in as well trying to build up some muscle mass again. Been doing moderate weight 4?sets of 15 reps per excercise and up to 4 different excercise per body part. Started with 2 days on And rest on the next day. My problem is i cant get a straight answer anywhere as to what’s an acceptable place to start.

Hi Neil, Thanks for your comment. I’ve deleted your last name just to protect your privacy. I think when talking about something like Cross-Fit which is very high intensity, there’s not a lot of information yet in the medical journals as it applies to heart valve surgery. BUT, having worked for a number of years in cardiac rehab, I’ve seen lots of people go on to get back to normal, and then some. HOWEVER, while I cannot give any specific advice, one of the most important things I recommend to athletes is to work closely with the cardiologist and the rest of the medical management team (which might even include clinical exercise physiologists and nurses in the cardiac rehab settings). You may want to discuss having a treadmill stress test to see how you go at the higher exercise intensities. IF the docs are pleased with your performance on the stress test AND give you clearance to get back to high intensity Cross-Fit again, then fill your boots and get stuck into it. In closing, I’d just like to add that remember you’re only 2 months post op, so it’s still early days as far as your sternum healing goes. The soft tissue heals relatively quickly, but the sternum can take some time so be patient. Hope this helps give you some guidance. Feel free to stop back and leave another comment to let others reading this know how you’re doing and any tips you’d like to share from your experience. Cheers, Bill

Thank you, very helpful information. Partner has had open heart surgery 3 weeks ago. Very scared about level of exercise and worried if stitches can burst with too much up hill walking. It’s very scary and the information has helped a lot. Was very healthy beforehand and the surgery was needed because of infection. Replaced a main heart valve. Looking forward and hoping to do hill walking again.

Hi Amanda, Thanks for your comment. It’s highly unlikely that your partner’s stitches will burst with too much uphill walking. BUT, having said that, if only three weeks post-op, there should still be some restrictions on physical activity which the surgical team would have provided. Normally it is around a 6 to 8 week recovery time before full clearance to get back to higher intensity exercise. In general, limit uphill walking which can cause a sharp rise in heart rate and blood pressure, both of which can put stress on the heart when it’s trying to heal. It’s the same thing as if you have a broken leg. You shouldn’t go trying to run up hills when you’ve just had surgery to fix it. It takes time to get on even keel. Bottom line: speak with the cardiothoracic surgeon and cardiologist for specific recommendations relative to your partner’s medical history. But in general, once past that 6 to 8 week recovery phase, most people are given clearance by their doc to get back to doing higher intensity activities. Best to get that clearance just to be on the safe side. Hope this helps. Kind regards, Bill

Hi Dr Bill

I had open heart surgery 7 weeks ago to replace my aortic valve. As I read articles on the internet about post surgery exercise I’m getting rather concerned as I have hardly exercised these past few weeks. I talk walks now and again. I was not aware of the physio exercises to stretch my muscles etc. Is it too late to correct whatever damage that may have been caused by my lack of exercise? If not where should I start from.

Hi Natasha,

It’s never a bad time to exercise. Remember that heart valve surgery is really hard on the body so it’s not out of the ordinary to feel pretty exhausted afterwards (and not feel like exercising). Whilst stretching the muscles early on is advisable (with supervision of course), by now at 7 weeks post-op, your sternum should be feeling stronger. You might want to gently ease into some stretches around the shoulder girdle to help improve your range of motion, but remember to work within your pain threshold. If you stretch and you’re grimacing in pain, then you’re probably stretching too far. You want to feel the pull but not to the point where it feels like there’s an ice pick in your chest. If you’re now 7 weeks post op, I’d imagine you’re going to be seeing your doc again. It’s always a good idea to ask if you should be aware of any limitations on exercise specific to your medical history. If you can get into a cardiac rehab program, that’s also a great way to get good evidence-based advice and have proper supervision to put you on the right track. Hope this helps. Kind regards, Bill

Dr. Bill,

I’m turning 40 and had aortic valve replacement about 4 weeks ago now. Prior to my surgery I was an avid weight lifter and bench pressed 405 lbs (7 reps). I also squatted and dead lifted in the weight range as well. Cardio workouts are limited to quarter mile runs to warm up prior to lifting. I’m currently in cardiac rehab and don’t do any lifting over 7 lbs (cardiac surgeon stated nothing over 10 lbs). I’m also a police officer and won’t go back to full duty until late October. My question is will I be able to go back to the same type of workouts I used to do prior to surgery?

Hi J.R.G., thanks for your comment. In the immediate post surgery phase, it’s pretty much a standard recommendation to not lift much over 10lbs. Main reason is ensuring that your heart rate and blood pressure stay low while there is healing happening on the inside. As for going back to lifting heavy weights, the only person who can answer this question would be your medical management team (doc, nurses, cardiac rehab team etc). Everyone is different. I have seen people after valve replacement go back to some reasonably strenuous exercise, but ultimately it is going to be on the medical team’s approval (which will be specific to your particular medical history). The fact that you’re still reasonably young works to your advantage. Older adults with the same surgery and other comorbidities (like high blood pressure, diabetes, etc) would likely not be candidates for hard core workouts. Moving forward, I’d suggest speaking to your doc about having a treadmill stress test (when the time is right) to see how your ticker does under high intensity workloads. Granted it is not weight lifting, but if you’re able to tolerate very high workloads under controlled circumstances, then it may help you plead your case for getting back to lifting heavy again. Plus you’ll probably want to have regular checkups to ensure that the valve is holding up well and there are no other issues which might make weight lifting unsafe for you. I think heart surgery is often worse for people who are physically active because it’s not a case of convincing you to exercise, but instead convincing you to take it easy while there is healing happening on the inside! Bottom line: have a talk with your cardiac rehab team and docs/nurses and ask them what the likelihood is of getting back to your routine. Feel free to stop back and post another message, as your story can give hope and inspire others going through the same thing. Cheers, Bill

doc, my name is rock i had pig valve replacement of my aorta in 2015 my question is can i use pre workout supplements before workouts, and could u please email ur answer thanks ahead of time doc

It depends on what’s in it. Best to discuss with your cardiologist.

Hi Dr. Bill,

I am 41 years old and I had a Mitral Valve Replacement (mechanical) and a Tricuspid Valve Repair and had a pacemaker put in because my heart wasn’t working. It’s been almost 3 years since my operation and I am still having a little discomfort at times where my scar is and sometimes would get sharp pains that feels like a shock in the same area. The pain isn’t severe but it’s enough where it stops me in my tracks for a good 10 minutes. I work graveyard shift and my job description is cashier/stocker. And I’ve noticed that lately I tend to get weak and tiresome very easily. Is that normal? I get about 6 to 7 hours of sleep a day 3 1/2 hours in the morning then 2 1/2 to 3 hour in the early evening. If not that sometimes less then that at times. I did have graves disease but took the Radio-active Iodine and now have Hypothyroidism. I get my INR and pacemaker checked regularly and everything is fine there. I’ve tried talking to my cardiologist about this but he’s no help. I am currently taking Warfarin, Carvedilol, Levothyroxine and recently started taking Norethindrone Acetate to control my menstrual bleeding. Due to loss of alot of blood which led to needing a blood transfusion last month.

Hi Nicole,

I’ll preface my comments by saying that I can’t give any medical advice since 1) I’m a clinical exercise physiologist; and 2) this is the internet and I’m not directly involved in your medical care.

Based on what you’ve written, there are a lot of medical issues happening all at the same time, so it is very difficult to pin it down to one thing. Given that your heart valve surgery was three years ago and was presumably successful, I wouldn’t think it was cardiac related (theoretically possible, but unlikely). You’re dealing with hypothyroidism and taking a combination of medications. In particular, Carvedilol has been associated with fatigue/tiredness in some people taking it, so you might wish to talk to your primary care physician for a proper consultation, workup, and evaluation of your medications (if appropriate). I’m also wondering what your blood pressure is. If you’re bleeding a lot and your blood volume is low, this could plausibly lower your blood pressure and make you feel a bit lethargic. Also, heavy bleeding could contribute to iron deficiency which might also explain why you’re feeling like you are. In short, there are a LOT of moving parts here and you don’t want to play guessing games. Best bet is to get a proper consultation with your doctor and try to work out the culprit for your tiredness/fatigue. Hope this helps. Kind regards, Bill

One year and gone through mvr, what is healthy lifestyle including exercise and diet?

I’ve included exercise guidelines in this article. For healthy eating, a Mediterranean style diet is known to be heart healthy.

Dear Doc, I am 55 years old and 2 weeks ago my doctor send me to a cardiologist and the report says I have AS and AR. I have to go for AVR.

I was a sportive person and playing squash tennis regularly. Now shall you advise can I play now. My doctor says no and only do walking 30 minutes in daily. The surgery may take place within 3 to 6 months time. please advise what can be do in good exercise for making heart in stable.

Hi Joseph,

I cannot authorise you to do anything above the word of your doctor. There may be specific medical concerns where doing exercise may not be in your best interest. I would suggest discussing what you can do AFTER your surgery with your doc and working back up to playing high intensity sports after you’re healing up. You might consider asking your doctor if you can do more than 30 minutes, maybe up to 60 minutes in order to get as strong as possible going into the surgery. More than likely, at this particular time, high intensity exercise may not be the best thing for you. Hope this helps guide you in the right direction. Kind regards, Bill

Hi Dr. Sukala,

I am a 60-year old ex-pro cyclist from the 70s and 80s and at 14-months ago found I had a bad aorta bicuspid valve since birth but somehow raced with it.

I looking for advise from an expert on how hard, deep and long I can train with my pig valve. I feel great but no one can give me information or advise about training at my age and limits if I have any.

I am glad to pay because I have been blessed and can afford an expert to work or consult with me on my limits if any (LOL).

Hi Erik

Thank you for your question. As every person’s situation is unique, I’d suggest you speak with your cardiologist about having a stress test performed to see how your heart goes at very high workloads. After that, I’d recommend getting a referral for a cardiac rehabilitation program that uses telemetry monitoring and see if they can check out your ticker at different intensities and durations. Both the stress test and regular tele monitoring at the cardiac rehab will give you a treasure trove of information on how your heart rate, blood pressure, and rhythm respond to different workloads. You can use this information to inform your non-cardiac rehab training sessions. Hope this helps. Kind regards, Bill

Hi Doc,

I really appreciate your informative website. 3 weeks ago I had an aortic valve replacement with Bovine tissue. I am healing faster than expected and walking over 3 miles each morning. I am a 54 yr old Firefighter/Paramedic that worked out regularly.

Now while healing, they have me on coumadin and a beta blocker and pepcid. I also take vitamins.

I read your comments about lifting weights, but have read nothing about doing sit ups. How soon can I start working my abdomen?

Thanking you in advance for your rapid response.

Alex

Hi Alex, Thanks for your comment. Wow, you are healing at Superman pace! But just remember, even though you might feel well (which is a good thing), there IS still healing happening on the inside, so it’s important not to go too overboard at this early point in the recovery.

In answer to your question, I would first suggest speaking with your doc or cardiac rehab team (if applicable) about clearance for more strenuous exercise. If you are given clearance and they green light you for sit-ups, then it would just be a case of starting off with limited range of motion crunches and gradually working up to higher intensities as tolerated.

I also note that you are on a beta-blocker medication, so the will help keep your heart rate and blood pressure down a notch, thus making exercise a little safer for you. Bottom line: 1) get clearance from your doc or cardiac rehab to do more strenuous exercise; 2) ask if there are any specific limitations they’d recommend and for how long; 3) start with limited range of motion and work up slowly to a higher level of difficulty as tolerated; 4) pay attention to your body and any signs or symptoms. If you feel any pain as in, “OUCH, THAT HURTS!” then that’s your body telling you to ease up a notch.

By about two months post-op, you should be feeling much better. Feel free to stop back and leave another comment so others can learn from your experience.

Kind regards,

Bill

Thank you, your feedback is insightful. Unfortunately I don’t have a rehab team. Living in a small town makes getting appointments futile to the pace of my recovery.

A year ago I underwent a TAVI procedure for severe aortic stenosis through the femoral artery. I was very fit as I had always walked every day and was discharged from hospital the following day. I completed the cardio rehab course and have continued my daily walk ever since. I would like to know if its safe to now start walking on a treadmill. Many thanks. Irene

Hi Irene

As long as you’re medically stable and you have clearance from your doctor to exercise, realistically, you should be just fine. You mention that you have completed cardiac rehab. If you tolerated that well and without any issues then that is also reassuring. Bottom line: if you’re cleared for exercise by your medical management team, then you should be safe to walk on the treadmill. Hope this helps.

I am 67 y female. My dr. Referred me to a cardiologist because I was short of breath 2 times in the past 6 months. I feel fine and walk 5 days a week and previously swam 25 laps 5 days per week. I have just had tee and r and l catheterization. The results show a severely leaking aortic valve and a moderate/severe leaking mitral valve. I don’t feel bad and my fear is if I have surgery that I will never get back to how good I feel now. What are the risks if I choose not to have surgery?

Hi Jean,

Thanks for taking the time to leave a comment. I can certainly understand your concerns. While I cannot give any advice or make any recommendations either way, here are some points that would be worth discussing with your cardiologist.

1. While it’s been objectively determined that your aortic valve and mitral valves are leaking, to what extent is your fitness “protecting” you and compensating for the leaky valves?

2. How much longer does the cardiologist think you can go without having the surgery? At some point, you will likely have to have the surgery, but only your cardiologist can give you a more firm answer in this case.

3. Does your cardiologist and/or surgeon think that they can repair your valves rather than a full replacement? If it’s possible to repair them rather than replace them, then this might be a good option in the long-term.

4. If you DO decide on having the surgery, ask if there are any options for minimally invasive surgery INSTEAD of having the full sternal sternotomy. Have a look at this article to get a better understanding: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4191712/ or Google “minimally invasive valve surgery” and inform yourself of the options currently available.

Overall, you will probably find that, if you can have the minimally invasive heart valve surgery, then your recovery time will be much quicker and the overall stress on the body will be less. AND, if your valves are working well (either repaired or replaced), then you will most definitely feel much better (i.e., no shortness of breath etc which may get worse with your worsening valves).

Hopefully this information is helpful, but feel free to stop back and leave a comment again if need be.

Kind regards,

Bill

@Jean LaPietra, Get your surgery done if your cardiologist recommends it. There is a test that gives numbers that tell when is the best time. I had my mitral valve repaired at Cleveland Clinic in Ohio in 2011. Fatigue is what triggered my attempt to research this. The procedures that are done now are extremely safe and the outcomes are 99% plus effective. Mine was done robotically.

If you have a mechanical valve can you use the legxercise

Dear Dr Sukala,

I had aortic valve replacement surgery on 1 September 2021 (just under 4 weeks ago). I had an upper mini sternotomy performed with a bovine replacement valve used to replace my leaking/regurgitating aortic valve. I’m 75 and in general good health and have lived a active lifestyle and would like to resume that same level of activity as soon as possible. I plan on engaging in a regular cardiac rehab program starting in 2 weeks. Currently I’m walking twice a day in the neighborhood (roughly a mile each session/ 2 miles each day ). Using my fitbit, I’m keeping my BPM under a 100 BPM level. My question is, a lot is said about the healing of the sternum and how low long it takes to heal, but little is mentioned as to how long it takes to heal the heart itself and the precautions moving forward? I do have plans to resume lifting weights and returning to regular exercise!

Thank you,

Jim Lyon

Hi Jim,

Thanks for taking the time to leave a comment. Great question. I think the answer to your question would really depend on the specifics of the open heart surgery itself. But, aside from any sternal discomfort, on average, most people feel reasonably well and back to normal by around eight weeks after surgery. There may still be some soft tissue healing happening on the inside but most patients I’ve worked in cardiac rehab with tend to be able to get back to doing most things without any worries by that 2-month mark. Ultimately, you’d have to speak with your surgeon and ask what an expected time frame is for full healing in your case.

On a positive note, I’m very happy to see that you’re going to start in a cardiac rehab program. It looks like you’re an active person so you’ll likely benefit from it to get fine tuned to your body post-surgery to ensure that you’re progressing as safely as possible.

Regarding weight lifting, if your cardiologist deems you stable and low risk, I don’t think you should have any issues doing resistance training (notwithstanding extremely heavy powerlifting or other things that might warrant special consideration).

You’re on the right track and taking all the correct precautions. From here, it’s just a matter of time until you’re feeling like your old self, or possibly even better now that you have that new valve working for you! Hope this helps.

Kind regards,

Bill

Hello Dr. Sukala. I know you can’t give me medical advice over the internet, but I’m hoping you can suggest some new ideas for my doctors and me to explore about the mystery we’ve been trying to solve for more than two years. Here’s the shortest version of my long saga:

– doctor heard a murmur in mid 2019

– diagnosed with severe MVR

– no symptoms…at 47 I could run as many 8-9 minute miles as I wanted and my resting HR was 49

– decided to do a repair, open procedure that was done in August 2019

– repair seemed to go great (four sets of neochords with a 32mm Edwards Lifesciences ring…I was walking ten or so miles a day four days after surgery

– I did have aflutter four weeks after surgery and was cardio-converted but that was attributed to the trauma of the surgery

– got clearance to run again six weeks after surgery…I was off all post-operative medications by this point

– I took my time running again but it quickly became clear that something was wrong. I would be short of breath almost immediately after starting and could barely run a single 12-minute mile. I tried all sorts of training approaches for months but never really improved. After I stop running totally out of breath, my HR will usually drop really quickly…as much as 40-50 bpm in the first minute after I stop running.

– stress echos and even a stress MRI all showed “normal”

– We finally found on a TEE that I still had a “eccentric jet” of MVR along with SAM…my surgeon said the bad news was I needed another surgery but I was actually happy if it would fix the problem I never had in the first place

– second surgery (Dec 2020) also seemed to go well, but my symptoms are barely better to this day. I can run maybe one 9 or 10 minute mile but I’m struggling to breathe the entire time and can barely finish it. My resting HR is now in the mid-60s and has been since the first surgery

– it was found during the second surgery that the tissue where the neochords were anchored had stretched, so my surgeon added five more sets of neochords between the original ones and anchored them into a thicker part of the muscle. He also lighted my LAA since I’d had aflutter after the first surgery.

– I think I’ve had every test known to try to diagnose this, and I’ve closely monitored all my exercise to try to figure this out.

– one strange thing I’ve noticed is that my heart rate seems very “reactive”…it would spike to 140 if I just went up one flight of stairs soon after the first surgery. I still “feel my breath” just casually walking up a flight of stairs. When I run, though, it will usually never go above 140 and is sometimes as low as 105 when I’m barely able to breathe after a tough hill mountain biking. The few times I’ve seen it go into the 160s or so, I usually feel a little better while running. I don’t get the gradual build of my HR to a steady plateau like I used to…it seems to go up and down minute-to-minute between a pretty narrow range of 110-140 bpm. Again, this is all without any medications like beta blockers, etc.

– all the TTEs and TEEs indicate the repaired valve is good

– I’ve had cardiopulmonary exercise tests showing 34.5 VO2 Max and the only abnormality noted was “abnormal ventilatory efficiency slope” so we looked into pulmonary hypertension

– I recently had a right heart catheterization with exercise that ruled out pulmonary hypertension. VO2 Max was 30.5 at the end of the protocol but my HR was only 108 at that point – I went past the protocol and had to spin double the Watts called for to get my HR up to the range where it is when I’m trying to run.

Sorry this is so long, but I wanted to give you at least the outlines of this long saga. Overall, it feels to me like my HR is not “responding to demand” quickly enough. Not sure if that’s “electrical” or “plumbing” related. I also found this article (link below) recently that seems to indicate problems like mine could be related to the actual incision in my LV for both surgeries. That might explain one of the most confusing parts of this for me – the fact that, even though the first repair failed, fixing that problem didn’t really change my exercise intolerance. If the problem was (coincidentally) related to the incision in the first surgery, that might explain the disconnect between the actual valve repair and my ability to exercise. The reality is that I was running as much as I wanted to with severe MVR before any surgeries, so maybe this isn’t directly related to the valve itself.

Please let me know if you have any other ideas for my doctors and me to explore or if you’ve ever encountered anything like this in your practice. Thanks!

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/41/Supplement_2/ehaa946.3085/6002340

Hi Olivier,

Thanks for taking the time to leave a detailed comment to explain everything you’ve been through, and you’ve clearly been through a lot over the past few years. I’ve seen a lot of strange things in cardiac rehab but I haven’t come across the exact same thing as your situation. However, as I was reading through your history, the thing that kept coming to mind was that the first surgery might have caused some degree of nerve damage related to chronotropic incompetence. In looking through the article from the link you posted, the authors explicitly mentioned that the “left atrium incision impairs cardiac sympathetic nerves and causes CI…”

I can certainly empathise with you that this must be massively frustrating because it seems the treatment left you worse off than you were in the first place. While I can’t make any comment on the decision to operate, many of the cardiologists and surgeons I’ve worked with have said that if someone is asymptomatic, then it’s sometimes a better option to just monitor over time UNTIL they become properly symptomatic and THEN consider surgical options. Though having said that, there may have been other extenuating circumstances that could have contributed to the recommendation for surgery. In any event, you’ll still need to deal with what’s right in front of you right here and now.

I think you drew the same conclusion that there was some sort of electrical disruption within your heart and, while it’s good that all the other tests came back within normal limits, it would seem that moving forward, it might be worth having a look around for an electrophysiologist, a cardiologist who specialises specifically in cardiac rate and rhythm disorders. I’m not exactly certain what the best course of action would be at this stage but it would certainly be worth your while to get a consult with an electrophysiologist to put all the options on the table. Structurally, based on the information you’ve provided, your heart seems to be ok, but it’s just the electrical innervation seems to have been disrupted.

I don’t know if that moves you in the right direction, but I really couldn’t give you much more information than that. But the more information you can get, the better at this point, especially since you are still young and quality of life is a major factor moving forward (and particularly because you’re an active person).

Feel free to stop back and leave another comment later on after you’ve had more evaluations. The information you provide here may benefit others going through the same or similar situation.

Kind regards,

Bill

Hello Doctor

My name is Khalid Khan and I am 22 years old as of 9 week ago. My aortic valve has been replaced and now I feel better, but I have some questions. Actually I like running exercise and I want to run 1 mile in 7 minutes. I discuss it with my doctor but he says jogging is better exercise than running. What Is your opinion on this?

The second question is that my left ventricle has become dilated. Will this require any medication?

Hi Khalid,

Thanks for your comment. As for whether running is better than jogging, or vice versa, the answer is: it depends. If you’re in recovery, then I suggest working from lower intensities to higher intensities as you progress through the recovery period. But once you’re recovered and with approval from your medical management team, there’s no good reason why you should not be able to run again, so long as it is not causing any signs or symptoms related to your heart or the surgery. I’ve worked with elite athletes after open heart surgery and they were able to safely exercise at high intensities again but, as I said, only after discussing the matter with their doctor and working together to ensure the medications were not impacting their ability to exercise.

As for a dilated left ventricle, I really can’t answer that because every case is different. Only your doctor (being intimately familiar with your situation) can answer this. But as I mentioned above, I think it is important to work closely with your doctor to find the right medication and the right dose so that it doesn’t affect your quality of life and ability to exercise (which sounds important to you).

Hope this helps.

Hi Dr Sukala,

Thank you for publishing this. I was excited to see some sort of reference for the topic… finally!

I have a question about the ability to fully regain one’s prior aerobic endurance after surgery, and your opinion of what might be the obstacle preventing this.

For background, I had my surgery 9 years ago. I’m currently a 41 y.o. male. I had a mechanical aortic valve installed to replace my tricuspid valve, along with a prosthetic to replace my ascending aorta due to a developing aneurysm.

Prior to surgery, I was a marathon runner. To this day I continue to run/ lift weights about every day. There’ve been no negative health events or symptoms since surgery. But I’ve never regained my running endurance. I run about 2 miles/day, which is about the max distance I can achieve. Nothing close to what my performance was prior to surgery.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on why this might be. Would the cause be the mechanical valve and/or the prosthetic and in equal parts?

I’ve had several theories, but the prevailing one is that with all this hardware, I’ll never achieve the same blood flow as what my natural aortic valve and aorta could achieve.

Medical staff over the years really haven’t had any info to share with me, so I’d be incredibly grateful here. It’s been a daily reminder that I’ll never get any of my former abilities back, and it’s difficult not knowing the physical cause. It’s not for a lack of effort, haha.

Best,

Wade

Hi Wade,

Thanks for taking time to leave a comment. You raise an interesting question and, as you’ve heard before, it’s hard to know exactly what might be causing your reduced endurance. Aside from the mechanical valve itself, are you taking any medications that could be affecting your exercise capacity? What you’re describing is a common complain from beta blockers. But in the case of valves, blood thinners are often prescribed. However, I’m not sure to what extent your blood thinners (if applicable) could be affecting your ability to transport oxygen in the blood. I think this might be a question to run by your medical management team and see if there could be any connection.

Sorry I can’t provide much more than that, but I think it is definitely a good question worth probing further.

Cheers,

Bill

@Dr Bill Sukala, Thanks so much for the reply! I was really excited to see it. Yes, I’m on 10mg of warfarin daily. It’s a mystery for sure, but a happy one. I’m far more grateful to still be active and in overall good health. Thanks again!

Hi sir,

It was an in-depth explanation of post op exercise guideline.

I m Meet Desai, I’m 44 a regular fitness freak and a sports person. I had a leaky mitral valve and it was replaced through surgery. Its been 10 weeks and my rehab and recovery sessions are going on nicely. Started going to gym and started weight training with minimal weights, and increasing gradually while keeping checking on heart rates. Right now target heart rate is 143 bpm and recovery heart rate is 30 bpm in 1 min.

I wanted to ask, when can i start my sports activities and, for that, when i can start training?

Thanks.

Hi Meet,

Thank you for sharing your progress—it’s fantastic to hear that your recovery and rehab are going well! It sounds like you’re taking a thoughtful and measured approach to your fitness, which is a great way to support your long-term heart health. Let me address your questions below:

Returning to sports and training

At 10 weeks post-surgery, your body is still healing, so it’s important to work closely with your doctor and medical management team before resuming sports activities or more intensive training. They are best positioned to assess your recovery progress and ensure it’s safe to gradually increase the intensity of your workouts.

When your doctor feels the time is right, you might consider undergoing a high-intensity treadmill stress test. This test can provide valuable information about your heart rate and blood pressure response during exercise, and your cardiac rhythm (via ECG monitoring). The results will help your doctors offer personalised recommendations for safely returning to sports and higher-intensity training.

Monitoring heart rate

It’s great to see that you’re already monitoring your heart rate during workouts. Your target and recovery heart rates are helpful benchmarks, but keep in mind that your heart may still be adapting to the changes post-surgery. Gradual increases in activity, as you’re currently doing, are ideal for ensuring steady progress without overtaxing your cardiovascular system.

Final thoughts

Every recovery is unique, and your timeline for resuming sports will depend on your individual healing and how your heart adapts over time. Be sure to communicate openly with your healthcare team, as they can guide you in creating a plan that aligns with your fitness goals while prioritising safety.

Wishing you continued success on your journey back to health and fitness. Feel free to check in with any updates or additional questions!

Warm regards,

Dr Bill