Choosing a personal trainer in can be a daunting experience.

Who is best qualified to help you? Who will deliver excellent service in the most safe and effective way possible?

In this post-truth age of social media-driven misinformation like “alternative facts” and “fake news,” lots of maverick trainers out there literally make up whatever training or nutrition theories they want, with no research evidence to back it up, wrap a marketing campaign around it, and then demand critics “prove them wrong.”

To be clear up front, this is not a hit job or a scathing indictment against personal trainers.

Quite the contrary, there are excellent trainers out there who stick within their scope of practice and transform peoples’ lives.

And it’s sad that their good reputation is being sullied by the presence of maverick trainers who are in way over their heads in professing knowledge they don’t have.

In this guest post by professional strength and conditioning coach Dr Dan Jolley, he discusses the research around personal trainers’ knowledge and skills against the backdrop of their perceived level of knowledge and skills.

He’ll then provide practical tips you can use to find a qualified trainer best suited to help you meet your goals. Over to you Dr Dan! –Bill

Hiring a personal trainer: hasn’t this been covered before?

There are plenty of articles giving you good advice on how to find a personal trainer.

Some of the advice is excellent (check out these articles here and here if you want to read further), but it’s an evolving landscape out there and it’s not just a simple case anymore of “find someone who is registered or certified.”

There are about 20,000 registered personal trainers in Australia (and, unfortunately, plenty more that aren’t registered), so there’s plenty of choice.

But we’re going to take a slightly different angle on choosing a trainer.

Not just what the trainer knows, but what they think about what they know. In fact, this could be the most important thing you find out about your personal trainer.

But firstly, what recommendations are already out there?

Choosing your personal trainer

Here is a quick 7-point tick list for choosing a good trainer:

Are they qualified?

A Certificate IV in Fitness is the minimum standard for a personal trainer in Australia, though some have university exercise science degrees.

Are they a Registered Exercise Professional?

If the trainer turns up in Fitness Australia’s register, you can at least be sure they have the minimum qualifications.

You can also see what professional development they have done (though this is self-reported).

Do they have the appropriate insurance?

A minimum standard is professional indemnity and public liability insurance.

Do they outline fees & charges up front?

Standard advice in any industry. Make sure you know how much you are spending. Also ask about any refund or cancellation policy.

Are they capable to delivering the type of training you are after?

If you have specific requirements due to injury, age, or unusual needs (i.e., uncommon diseases), can the trainer meet these needs?

Some people may need a trainer with more advanced qualifications and specialty knowledge.

Do they perform a pre-exercise screening?

This is a limitation for many trainers.

This is not just a bit of paperwork, or a coffee and chat about what you want to achieve.

This should be an in-depth, documented discussion of your exercise, medical, and injury history.

Standard screening tests should be performed, as well as a movement screening, strength, or fitness testing as appropriate.

You should be referred to a general practitioner or allied health professional if necessary before you begin training.

Do they operate within their scope of practice?

If a trainer encourages the use of fat blaster nutritional supplements, plans highly restrictive diets, offers professional sports coaching, or claims to be able to diagnose or treat injury or illness, they are practising outside their scope of practice.

I address this issue in my previous article on spot reduction in which I tackle exercise misconceptions that refuse to die.

What else should you know about your trainer?

Something I would like to add to this list of recommendations, however, is “make sure your trainer is aware of his/her own limitations, and is not overly (arrogantly) confident.”

There is no shortage of personal trainers out there willing to tell you they are an “expert” in their field.

They may tell you they are up to date with the latest science of exercise and nutrition and are absolutely cutting edge. But are they?

It’s unlikely unless they have a postgraduate research qualification (i.e., honours, masters, or doctoral degree in a health science discipline) and are able to read/comprehend complex biochemistry and physiology, interpret statistics, and then put the results into practical context.

The information presented to students as part of a personal training qualification is often a distilled and simplified interpretation of large and complex bodies of evidence across multiple health science disciplines.

Personal trainers may pick up a lot of additional knowledge by attending professional development courses, but they are still relying on experts in their respective fields (such as physiotherapists, dietitians, exercise physiologists, psychologists, etc.) to interpret the information and provide the context and perspective relative to the personal training field.

How much does your personal trainer know?

There’s surprisingly little research about the knowledge of practicing personal trainers, so to answer this question we must rely on international studies.

Results from a small qualitative study in Switzerland (which does not require personal trainers to be registered) found 85% of personal trainers possessed the required qualifications (with 12% having a university degree), but many used poor practices, or operated outside their scope of practice (such as prescribing supplements when providing nutritional advice).

Furthermore, 73% of trainers did no follow up on the nutrition advice, which is unfortunate considering how unsuccessful the majority of weight loss attempts are.

While 62% did some ongoing reading or self-directed education, fewer than 20% attended a conference or course.

However, this doesn’t tell us about the quality of the information to which they are exposed.

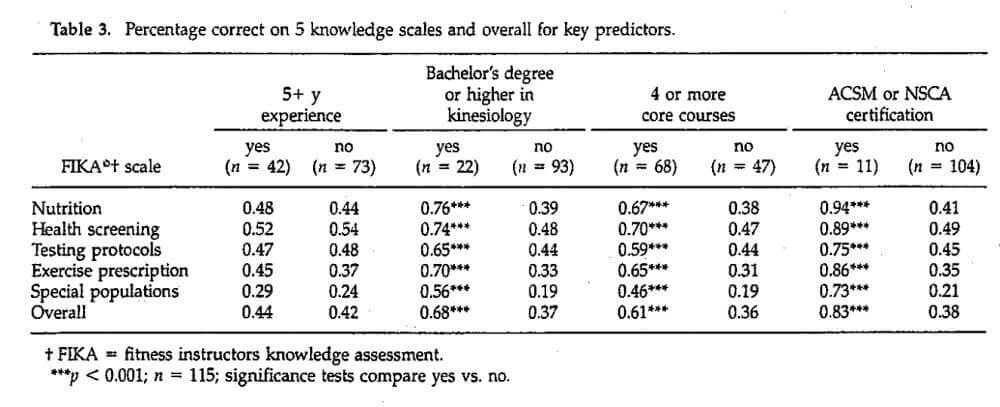

A survey of 115 trainers in the US found that personal trainers with a bachelor’s degree in exercise science and certification by American College of Sports Medicine or the National Strength and Conditioning Association as opposed to other certifications were strong predictors of a personal trainer’s knowledge, whereas years of experience was not related to knowledge.

Another US study from 2015 found similar results, with personal trainers demonstrating poor knowledge of exercise prescription guidelines.

Neither study found that the length of practice of a personal trainer improved their knowledge.

This is important, as experience is often seen as a substitute for formal education in the fitness industry and is sometimes more highly regarded than education by many personal trainers I have met.

What has been shown to improve knowledge is the level of qualification the trainer possesses.

So maybe we can consider this when choosing our trainer.

Do they have, or are they in the process of completing, a university exercise science degree?

Following on from above, it’s worth mentioning that in the United States, no university degree or formal training is required by law to become a personal trainer.

For some certifications, you can read a book, memorise as much as you can, and then take the exam. If you pass, then you’re a personal trainer.

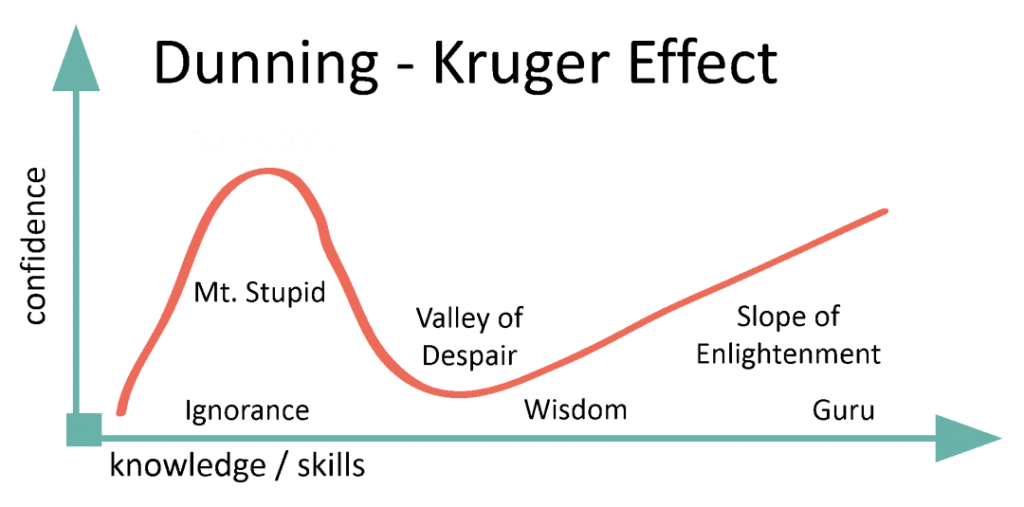

An alarming finding of the 2015 study was the unfounded confidence that most of the trainers surveyed possessed.

When asked to rate their knowledge after completing the test, only 7% of the trainers thought they knew less than half the answers.

This is despite an average score of 43% in this case!

More than half the trainers surveyed thought they knew “most of the answers”, though more confidence didn’t relate to better test scores!

The Dunning-Kruger Effect: the less you know, the more you think you know

In 1995, McArthur Wheeler robbed a Pittsburgh bank in broad daylight, in full view of security cameras, without an apparent disguise.

But when arrested later that day, he was shocked that he had been caught.

After all, he had rubbed lemon juice on his face. For some reason, Mr Wheeler thought that this would make his face invisible to security cameras!

While most of us would shake our heads at his stupidity, two Cornell University researchers were intrigued at how confident he had been in his (obviously flawed) knowledge.

They wrote a paper entitled Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments.

The phenomenon they described became known as the Dunning-Kruger Effect, which suggests that a certain amount of knowledge is required for someone to be aware of their lack of knowledge.

For a personal trainer, a small amount of education could make someone confident that they are ready to go into the industry and represent themselves as a fitness expert.

But someone with more education may also develop an awareness of how much more there is to know, and how incredibly complex a system like the human body is.

And though they are more educated and informed, they often do not express as much confidence in their knowledge.

Where does this overconfidence come from?

If you have a trainer already, you may be thinking “surely you’re talking about those other trainers?

My trainer is on the ball!” You may be right, but all of us – you and I included – are affected by errors in thinking that influence our confidence.

One of the major ones is confirmation bias.

This is when we interpret information in a way that supports our pre-existing opinion.

There may be no problem here if our pre-existing opinion is correct, but this isn’t always the case.

When our knowledge of a topic is limited, it’s probably wrong, or incomplete at best.

We then receive new information in a way that confirms our opinion and we become more convinced we are right.

This is how misconceptions form and strengthen over time, so you end up with people believing vaccines cause autism (they don’t), the earth is flat (it isn’t), or homeopathy works (it doesn’t).

Even armed with this knowledge of confirmation bias and how it affects your thinking, you are still prone to it.

Researchers have tried interventions to eliminate confirmation bias and none have been reliably successful to date.

The best we can hope for is to be aware of it, and examine our own thinking and attitudes for bias on a regular basis.

This also requires a willingness to admit our mistakes and be open to correction, which can be a challenge for many of us.

The attitude of your trainer is crucial

A study of personal trainers in the United Kingdom found that trainers would often behave in the fitness industry differently to how they were taught during their course.

They would do what their instructor required during the course then operate in whatever way they thought best once in the workplace.

While it is possible that these trainers were making better decisions than their instructors were, and interpreting information more accurately, this seems unlikely.

Admittedly, I’m relying on anecdotal evidence here – my eight years of lecturing in personal training courses makes me doubt the ability of these graduates.

More likely, they were overly confident in their knowledge and abilities for the reasons discussed above.

The same trainers saw on-the-job training and industry experience as important, but said cost would discourage them from attending formal professional development opportunities.

So the trainers prone to confirmation bias are not exposed to information that could lead them to correct their opinions.

And as has been shown in previous research studies here and here, industry experience is not always a reliable indication of the quality of your trainer. But even this finding may be rejected by trainers with a contrary opinion.

While years of experience may tell you how dedicated to their craft a trainer is, and qualifications may tell you how intelligent or well-read they are, it isn’t the whole story.

If your trainer is unwilling to accept that their opinions may be wrong, then it’s your health they may be putting at risk.

How to tell if your personal trainer is aware of their knowledge limits

A perfect opportunity to find out about your new trainer’s openness to evidence and change is the pre-exercise screening. If you have a medical or injury issue that will affect your training, what type of questions do they ask?

If your trainer wants to know which allied health professionals you have received treatment from, what remedial exercise, treatment, or medication was been prescribed, and what recommendations for ongoing management you have received, then you may have a good one.

If they ask you detailed questions about how you have managed your exercise until now, even better.

If they also want to discuss things further with other professionals, or do some extra reading, excellent! They get a gold star, and you have a trainer you can trust!

If, on the other hand, they don’t ask these questions, and are highly confident in their ability to treat or manage this issue, or are dismissive of the opinions of these qualified professionals, be sceptical.

Unless one of these professionals was a homeopath – their opinion can be dismissed immediately.

In closing, the moral of the story is make sure your trainer is well-qualified, aware of their own limitations, and not proudly standing on top of “Mount Stupid.”

There is a lot that you have to look for when choosing a personal trainer. However, do l do like that the article reminds readers that their attitude is important as well. For example, if you are on a weight loss program you will want to make sure that they can help you and consult with you on it.

Great insight into what a personal trainer actually knows. There are many local people (working out of Dublin, Ireland) claiming to be qualified in PT, S&C and nutrition that are simply not the case.

Cheers Darragh, yep, it’s still the Wild West in the fitness industry. Social media has been like petrol on the flames of misinformation where anyone with a pulpit can spout off their own brand of nonsense. Keep up the good fight for evidence-based information.